Kiss My Grits

I Miss You Grandma

Ever heard the phrase “Kiss My Grits”? It’s a nostalgic Southern expression meaning “Take a hike” or “I’m not putting up with your nonsense.” I first heard it from my grandmother, a proud South Carolinian who raised me in the Southeast Bronx while my mother worked long hours. My grandmother, a deeply religious woman, never uttered a bad word. But “kiss my grits” was her version of a cuss word—so when she said it, I knew she was truly ticked off. As I intentionally use this phrase now, I want you, the reader, to know that I’m cussing—albeit in a blessed, grandmother-approved way. She gifted me a way to express defiance without vulgarity, and for that, I’m grateful once again for her wisdom and grace.

While my grandmother’s use of the phrase resonates with me deeply, I’m fairly certain its pop culture fame came from the 1970s sitcom Alice, where Flo, a sassy waitress, used it to call out the foolishness of Mel, her boss. The phrase embodies playful dissent, and today, as I reflect on systemic inequities and the anti-DEI rhetoric swirling in current events, I’m also channeling Flo’s unapologetic energy. She will be my muse. So, to anyone dismissing systemic inequities and preaching perseverance and resilience to communities that already hold graduate degrees in resilience, I say, “Kiss my grits!”

The Allure and Limits of GRIT

If you work in higher education, you’ve probably heard of GRIT—a concept popularized by psychologist Angela Duckworth as the blend of passion and perseverance in achieving long-term goals. It sounds noble, right? Hard work, determination, and the so-called “American Dream” are core to our cultural narrative. But GRIT, like any concept, is not a cure-all. Even Duckworth acknowledges its limitations. She highlights how GRIT alone didn’t save personal relationships or resolve career struggles; she needed support systems and opportunities. When resilience is touted as the magical solution to systemic inequities, it becomes a shallow platitude.

Furthermore, Duckworth admits that GRIT isn’t the sole driver of success. External factors—what she references as the “power of the situation”—are equally important. For example, suggesting that someone born into generational wealth has overcome the same obstacles as someone raised in poverty is not just absurd—it’s deeply insulting. Despite all of his education, wealth, and resources, RFK Jr. is a dangerously powerful, oblivious ignoramus. To him and any others peddling this notion—kiss my grits.

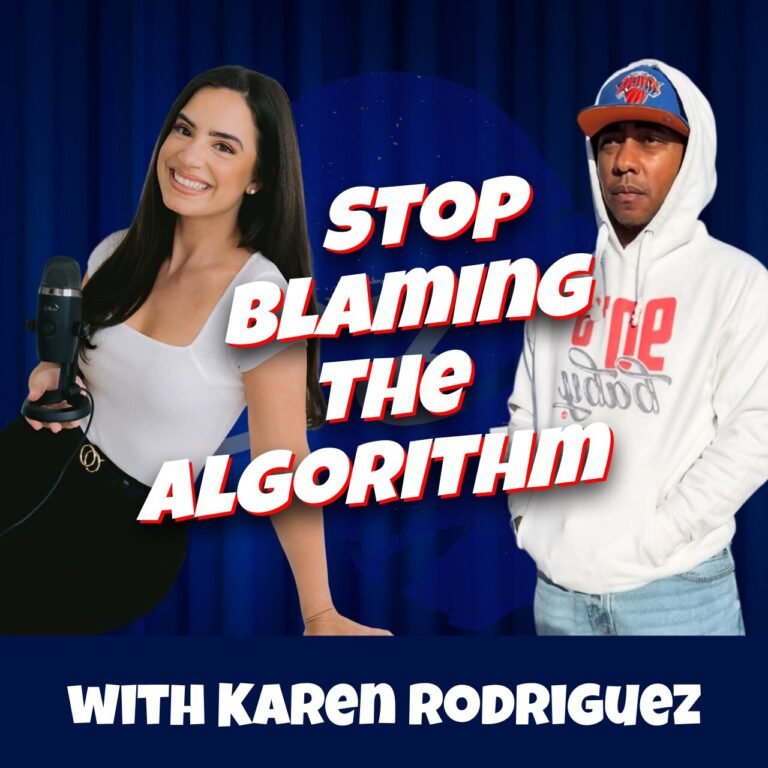

I hear my own heart in Roland Martin’s recent fiery response to RFK Jr.; it actually prompted me to write this post. RFK Jr. had the audacity to lecture Black professionals on resilience while forgetting to mention how he was the beneficiary of insane generational privilege—going back to his grandfather. The sheer nerve of him or anyone who has had every advantage preaching to individuals and communities that have faced systemic barriers for centuries is gaslighting at Avenger threat levels.

Yes, Irish Catholics faced significant persecution throughout history, particularly in the U.S. during the early 19th century. Anti-Irish Catholic sentiment, known as Hibernophobia, was both real and devastating to this community during that period. However, what RFK Jr. conveniently overlooks is that his success may owe less to the GRIT instilled by his family and more to the tens of millions of dollars that shielded and afforded his family countless opportunities. In doing so, he perpetuates a narrative about himself and others that fails to withstand historical scrutiny and common sense.

The Fickle Fashion of Educational Buzzwords

We in higher education have a penchant for trends. One moment, “self-esteem” is hailed as the magic bullet; the next, it’s “growth mindset,” and now “GRIT” dominates the discourse. It reminds me of that iconic scene from The Wiz where the Emerald City’s fashion keeps changing colors—green one moment, red the next. While entertaining, this relentless trend-chasing becomes counterproductive when influencers and leaders embrace new concepts with an “all-in” mentality, often accompanied by exaggerated posturing.

Buzzwords are frequently promoted as cure-alls but fail to account for their inherent limitations or prepare us for the necessary nuances. Research is undeniably essential, but the rush to implement new ideas—and for some to build their scholarly reputations—often leads to a disregard for the limitations of emerging findings. GRIT, for example, is undeniably valuable, but its applicability is far from universal. Overlooking these nuances results in disjointed practices and, frankly, wasted time and resources.

Instead of jumping on every educational bandwagon, we should pause to critically evaluate the context and substance of these concepts. Just a thought. Otherwise, we risk looking as foolish as those ever-changing fashionistas in The Wiz. To those who chase fleeting trends without depth or substance—kiss my grits.

GRIT Without Context

Telling students—especially marginalized students, and particularly poor, Black students—to embrace GRIT and resilience may seem empowering and coming from a good place. However, this narrative often serves to obscure systemic inequities, shifting the burden of overcoming these barriers entirely onto the individual. The injustice is glaring—not only did these students not create the problem, but they are also expected to solve it by surmounting an ongoing, deeply entrenched issue. Are you serious? Are these proponents misinformed, malicious, or simply delusional?!?

I make it a point to consume news across the political spectrum, but when I hear figures like Piers Morgan, Scott Jennings, Patrick Bet-David, and Ben Shapiro discussing these topics, I find myself genuinely questioning their motives. These individuals are clearly intelligent—so what explains their inability or unwillingness to recognize these realities? In 2020, the world witnessed the horrific, slow murder of a man by a police officer, broadcast in real time. Yet even that unambiguous atrocity remains a subject of debate. It’s not just frustrating—it’s profoundly disturbing and gross.

Celebrating GRIT without addressing systemic barriers sends a harmful and misleading message: the problem isn’t an unjust system; it’s you. This is like asking someone to climb a mountain while others are flown to the summit—absurd and infuriating. Expecting marginalized communities to “just work harder” or “run faster” without addressing the structural obstacles in their path is not only disingenuous but also profoundly cruel.

The reality is that there aren’t enough hours in the day for individuals to simply work their way out of dire financial circumstances, especially when policies are enacted to restrict overtime pay or strip labor protections. Seriously, what are we even debating here? Laws that further exploit workers while ignoring systemic inequities make it clear where the priorities lie—and it’s not with the people struggling the most. To those who continue to push this damaging rhetoric: kiss my grits.

Personal Reflections

As a Black male professional in higher education, I’ve lived this reality. I’ve been accused of engaging in “victimology,” “playing the race card,” or, my recent favorite, “trying to sound smart,” simply for defending my decisions, qualifications, experiences, and character.

Side note: Victimology. When someone offered this critique to me as a sincere olive branch of reflection (insert LOL here), I somehow managed to keep a straight face. Internally, I flashed back to the first time I encountered this term in John McWhorter’s book Self-Sabotage in Black America. For context, I strive to consume information from diverse perspectives; I’m deeply wary of echo chambers, regardless of who’s occupying them. This intentionality leads me to conservative radio shows, Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life, and McWhorter’s aforementioned book. While I vehemently disagree with their premises, arguments, and proposed solutions, I read their work as an exercise in both breathing control and grappling with opposing viewpoints.

Given today’s sociopolitical landscape, I’d be intrigued to hear McWhorter’s thoughts. In Self-Sabotage in Black America, his arguments hinged on three socio-ideological patterns within the Black community: victimology, anti-intellectualism, and separatism. Here’s a quick overview:

- Victimology: The irony is astounding when this critique is wielded in a sociopolitical climate where certain groups play the perpetual victim while actively working to dismantle civil rights protections.

- Anti-Intellectualism: This argument is almost laughable in the face of today’s rampant anti-intellectualism across broad swaths of society—particularly among those who weaponize disinformation while decrying critical thought currently sitting in seats of power.

- Separatism: McWhorter raised this concern in the context of a nation attempting to reckon with its past, but how can separatism be critiqued when communities remain effectively segregated by systemic design? Schools, neighborhoods, and opportunities still starkly reflect these divides.

McWhorter is undoubtedly brilliant, but like certain other intellectuals (Clarence Thomas comes to mind), I can’t help but sense an unresolved hurt in his heart that hinders him from channeling his immense intellect toward the greater good. His intellectual gifts are undeniable, yet his chosen frameworks often feel out of sync with the larger, more pressing realities we face today. That, however, is a deeper conversation for another time.

Perhaps this is why I so thoroughly enjoyed the debate when Khin Mai Aung, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Tim Wise handed John H. McWhorter, Terence J. Pell, and Joseph C. Phillips their proverbial hats during one of the earlier Intelligence Squared debates. The debate centered on the value and necessity of affirmative action, and the affirmative side delivered an unassailable array of powerful arguments and data to support its continued relevance in addressing systemic inequities. Who could have imagined, after such compelling advocacy, that 18 years later, the U.S. Supreme Court would dismantle affirmative action altogether?

The Court’s decision against affirmative action was a profound disappointment—a significant regression in the fight for equity. I wrote a reflection after the ruling, grappling with the weight of the decision and the larger implications for marginalized communities. Affirmative action was never a perfect solution, but it provided a necessary counterbalance to the pervasive inequities embedded in education and employment. Its dismantling leaves us with fewer tools to address systemic injustice, forcing us to double down on strategies that challenge these barriers in other ways. The disappointment of that ruling still lingers—a stark reminder of how much work remains to be done.

But folks still find it easier to blame Black people for lacking something—self-awareness of how to talk to people—as if we didn’t practically invent and perfect code-switching in the U.S. Despite all of this evidence, decades of data and anecdotal experience show less qualified peers seem to face fewer obstacles, are given greater latitude for errors, receive greater benefit of the doubt, are immune from co-opting ideas and work of others, and receive greater recognition. And there is more than enough data to show this to be systemic. But data truly doesn’t matter to some.

In fact, some are actively trying not only to delegitimize data but to erase it and stop companies and governments from collecting it. That is what the ANTI-DEI Act and Project 2025 aim to do: erase knowledge. Because if it’s hard to make the case to 73 million people when the data is publicly available and ready for people to see and judge for themselves, imagine a society that doesn’t have access to data or books or history. Divide and oppress. We see you. We know how this movie ends if this isn’t stopped by the will of the people, and there is time.

So yes, for those who were genuinely stunned that Vice President Harris’s qualifications were actually questioned in comparison to our felonious incoming president—yeah (I said what I said), this has been the daily lived experience for millions of Black people and other minority groups. The emotional toll of navigating these inequities is exhausting, and it’s meant to exhaust and then extinguish—be clear on that. To some conservative and liberal white women and Latinos…I’m still processing this, but I, along with half of the country, are deeply disappointed following November 5, 2024. However, I have been observing things in my own profession that have prepared me for the post-election data.

A different post, for a different time. Back to GRIT…where was I? (Breathe in—breathe out.)

Another conceptual example is Chris Rock’s comedy bit about his affluent neighborhood, which always hits home for me, and I have used it several times throughout the years as an educational tool: while some of us must move mountains, others only need to kick pebbles. The nerve of privileged individuals lecturing marginalized communities about resilience is infuriating. My success, though gratifying, is not a testament to GRIT alone. It’s also a product of timing, the support of others, and luck. I hear my grandmother’s words and want to honor her as well.

Faith, Luck, and A Tale of Two Crises

As I mentioned earlier, I was raised in a Christian household. In our home, “luck” was often replaced with the phrase “blessed and highly favored.” While I’ve struggled with my faith at various points in life—and that’s okay—it’s always been due to the notion of “greater than we can comprehend,” which often felt like a setup. That idea sometimes seemed designed to lull people into waiting for rescue when, in reality, we might need to be our own rescue squad. Still, I recognize that faith, when paired with positive energy and action, can offer immense strength during life’s toughest challenges. But I digress.

Dismissing the structural realities that perpetuate inequalities undermines the fact that systems are rigged. To those who suggest that Black Americans should “stop complaining” or “toughen up”—you know nothing. Quick history lesson to drive this point home—let’s use the crack epidemic and opioid crisis as examples. I’m an educator at heart – forgive me.

A Tale of Two Crises: Crack vs. Opioids

The government’s response to the opioid crisis has differed significantly from its approach to previous drug epidemics like the crack cocaine crisis of the 1980s.

Firstly, the opioid epidemic has been largely treated as a public health issue. Efforts have focused on expanding access to treatment, implementing harm reduction strategies such as distributing naloxone to reverse overdoses, and supporting recovery programs. In contrast, the response to the crack cocaine epidemic was predominantly punitive. The government intensified the “War on Drugs,” leading to increased law enforcement, mandatory minimum sentences, and mass incarceration, especially in urban areas.

Secondly, legislative actions and policies have reflected these differing approaches. During the opioid crisis, legislation like the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act of 2018 emphasized treatment, prevention, and recovery services. These laws received bipartisan support and aimed to address the epidemic through healthcare interventions. On the other hand, the Anti-Drug Abuse Acts of 1986 and 1988, enacted during the crack cocaine epidemic, imposed harsh penalties for drug offenses, including a 100:1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine. This led to disproportionately long sentences for crack offenses, primarily affecting minority communities.

Thirdly, media representation and public perception have played a significant role. Media coverage of the opioid crisis often highlights personal stories of addiction and recovery, fostering empathy and understanding. The narrative emphasizes that addiction can affect anyone, regardless of background. Conversely, media portrayal of the crack cocaine epidemic was frequently sensationalized, focusing on crime and violence. Terms like “crack baby” and “super predator” were used, stigmatizing individuals and communities affected by the epidemic.

Furthermore, demographics and racial disparities influenced the governmental response. The opioid crisis initially impacted predominantly white, rural, and suburban populations. This demographic shift influenced a more compassionate public and political response centered on treatment rather than punishment. In contrast, the crack cocaine epidemic disproportionately affected African American and Latino communities in urban settings. Racial biases contributed to the criminalization of these communities and a lack of investment in treatment options.

Additionally, the role of pharmaceutical companies versus street drugs is noteworthy. Prescription drugs played a significant role in the opioid crisis, with pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketing opioids and downplaying addiction risks. Legal actions have been taken against these companies for their involvement—leading to a $600 million settlement for those impacted. The crack cocaine epidemic involved illegal street drugs with no direct corporate involvement, but there have been allegations—though never confirmed—that the government was responsible for introducing these drugs as a way to fund the Iran-Contra conflict. During this time, the focus was on law enforcement efforts to curb the supply and penalize users and dealers.

Moreover, federal funding and resource allocation have differed between the two crises. Significant federal funding has been allocated during the opioid crisis for research, treatment programs, and prevention efforts. Grants and resources have been directed toward understanding and mitigating the epidemic. In contrast, during the crack cocaine epidemic, funding was primarily funneled into law enforcement and the criminal justice system, with minimal investment in treatment or rehabilitation services for affected individuals.

Lastly, the long-term policy outcomes highlight the divergent approaches. Policies during the opioid crisis have started to shift toward decriminalization of certain drug offenses and increased support for mental health services, reflecting a broader change in how addiction is viewed. The crack cocaine epidemic, however, led to long-term consequences like mass incarceration, community destabilization, and ongoing racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

The Absurdity of Anti-DEI Agendas

Recent legislative efforts to dismantle Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives epitomize hypocrisy. The “Dismantle DEI Act” claims to combat “reverse racism” while denying the existence of systemic racism. How can racism simultaneously not exist and require reversing? Make it make sense. It’s laughable in its inconsistency. Despite fiery critiques from our courageous Congressional representatives like Ayanna Pressley and Jasmine Crockett, the fact that such proposals gain traction is no longer alarming; it’s a “we don’t care about you or your experience” taunt. Some are now weaponizing civil rights language to undermine the very protections they claim to uphold, which is directly out of the Project 2025 playbook. To those advocating for these regressive policies—kiss my grits.

The Danger of Selective Memory

American society has a peculiar relationship with memory and historical events. We’re told to “move on” from events like January 6th but to “never forget” others, depending on whose narrative is served. This selective memory is not just hypocritical; it’s dangerous. I’ve witnessed friends face lifelong consequences for minor infractions while others escape accountability for monumental transgressions. This disparity reinforces systemic injustice, undermining trust in institutions. To those cherry-picking history to serve their agendas—kiss my grits.

Weaponizing GRIT Against the Marginalized

The GRIT narrative is being weaponized to critique marginalized groups. Lecturing Black communities on perseverance is not just tone-deaf—it’s insulting. We’ve shown resilience for centuries, navigating barriers most of these tough-talking loudmouths couldn’t fathom. When institutions use GRIT to shift accountability from systemic issues to individual shortcomings, they perpetuate injustice. GRIT should be celebrated, yes, but not a necessity for survival. To those misusing this concept—kiss my grits.

Moving Beyond Survival: A Call for Systemic Change

What’s the alternative? It’s far past time to dismantle the systemic barriers that necessitate extraordinary resilience and GRIT. Institutions must create environments where success is achievable without superhuman effort. This means implementing equitable policies, diversifying leadership, and fostering inclusive cultures. Celebrating GRIT is not inherently wrong, but it must come with an acknowledgment of systemic inequities. Let’s praise perseverance while working to eliminate the need for it. Anything less is superficial and unjust.

The path forward requires moving beyond resilience as a survival tool. Encouraging individuals to be gritty without addressing the inequities they face is a hollow gesture. A just society demands systemic change, not superficial solutions. Let’s challenge harmful narratives, hold institutions accountable, and create environments where everyone has a fair shot at success. To those standing in the way—KISS MY GRITS!

Questions for Reflection

- How can institutions create environments where students thrive without needing to rely on extraordinary resilience?

- Institutions must evaluate their policies, curricula, and cultures. Equitable practices, diverse leadership, and support systems are essential. Anything else is just lip service.

- In what ways can we celebrate individual perseverance while holding systems accountable for their role in creating barriers?